The Lady Who Became a Ghost Story: The Black Dahlia and America’s Most Haunting Mystery

She dreamed of Hollywood stardom. Instead, she became its darkest legend.

Los Angeles, January 15, 1947. The winter air was unusually crisp for Southern California. According to national weather records, the day’s low temperature fell to 38 degrees, and the high reached only 59 degrees, with clear skies and no rainfall recorded (Extreme Weather Watch). Under that pale winter sun, the vacant lots of Leimert Park stood stark and exposed. It was in one of those lots, on that cold morning, that a young mother pushing her baby carriage stopped in horror. What she thought was a discarded mannequin gleaming in the light was instead the mutilated body of 22-year-old Elizabeth Short. The discovery alone was shocking, but the press transformed it into something larger. Newspapers rushed lurid headlines such as “Girl Victim of Sex Fiend Found Slain” (Los Angeles Times, Jan. 16, 1947) and, in the competition for readers, seized on a nickname that would eclipse her own. Short had been rumored by locals to favor sheer black dresses, and with her striking dark hair, some had half-jokingly compared her to the noir film The Blue Dahlia released the previous year. Reporters amplified that reference until it became gospel, branding her forever as The Black Dahlia (FBI.gov; Los Angeles Times).

The young woman's body, gruesomely mutilated, lay in wait for an unsuspecting passerby; years later, its unsolved nature became a haunting sensation. Numerous contributing factors can be singled out as responsible for the failure. A component of the problem... The painstaking homicide investigation devolved into a public spectacle, with each detail distorted to capture headlines. Numerous occurrences suggest that this case may have gone awry. Consequently, the mystery has remained unsolved, intriguing people up to this very day. As the news buzzed with the supposed resolution of the Jack the Ripper murders, we observed no progress on our unsolved cases here in the US. The infamous Black Dahlia case, a chilling tale whispered through the city.

What should have been the beginning of a careful homicide investigation quickly unraveled into a contest for headlines. The crime scene itself was compromised almost immediately. “Reporters got there ahead of the police, and the press were traipsing through the crime scene, trampling evidence,” crime historian William J. Mann observed in his 2024 book Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood (Mann, 2024). The Los Angeles Police Department, already notorious for corruption in the late 1940s, found itself battling not only a lack of leads but a media machine more interested in selling papers than preserving evidence.

Detectives who worked the case admitted to the same. Sergeant Finis Brown later blamed the newspapers for contaminating witnesses, noting that many had been interviewed first by reporters rather than police. Harry Hansen, the lead investigator, recalled the frustration of competing with journalists who had resources and access his squad lacked. In a retrospective piece, the Los Angeles Times wrote that “almost every tabloid word turned up in the paper’s first story on the case” (Los Angeles Times, 2014).

The sensationalism created its own problems. Rumors about Short’s character — that she was a temptress, a nightclub habitué, a drifter with dozens of lovers — filled columns. Much of it was speculation, but it shaped the direction of police questioning. As historian Mary Pacios noted in Childhood Shadows, “The newspapers fed the police theories, and the police fed the newspapers leaks, until truth was almost impossible to separate from fantasy.”

Even the name “Black Dahlia” played a role in derailing the case. Once the nickname stuck, Elizabeth Short was no longer treated as a daughter or aspiring actress but as a character in a noir melodrama. The killer was cast as a shadowy villain, the victim as a femme fatale, and the investigation became entertainment. By the end of January 1947, more than 50 false confessions had been delivered to police, many encouraged by the publicity. The Examiner even ran extras boasting of “exclusive letters from the killer,” which turned out to be hoaxes.

📚 Draft Section: The Black Dahlia in Print

If the press distorted the case in 1947, authors have been reshaping it ever since. Nearly every decade since the murder has produced new books — some sober, some lurid, some outright fictional — each promising either a solution or a fresh perspective. Collectively, they’ve kept the Black Dahlia alive in the public imagination far longer than the LAPD ever could.

The earliest serious investigation in print came decades later with John Gilmore’s Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder (1994). Gilmore drew from LAPD files and his own proximity to the case to paint a chilling portrait of both Elizabeth Short and the Los Angeles of 1947. The book was praised for atmosphere but criticized for blurring fact and speculation. Still, Severed is often called the most influential nonfiction account, inspiring countless readers to revisit the mystery (The Horror Zine).

In 1999, Mary Pacios published Childhood Shadows, a more personal book that worked to humanize Short beyond the headlines. Pacios, who had known Elizabeth when she was alive, wrote against the tabloid caricatures. She argued that the press had effectively created a fictional persona, obscuring who Short truly was.

Fiction also played a significant role in mythmaking. James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia (1987) took the case into the realm of noir literature, imagining detectives consumed by obsession. Ellroy’s novel, a bestseller, cemented the case’s reputation as Los Angeles’s archetypal unsolved murder — even though it was fictional. The book became part of Ellroy’s “L.A. Quartet,” a literary exploration of corruption and crime in midcentury Los Angeles, and it influenced both the public imagination and Hollywood’s eventual film adaptation in 2006.

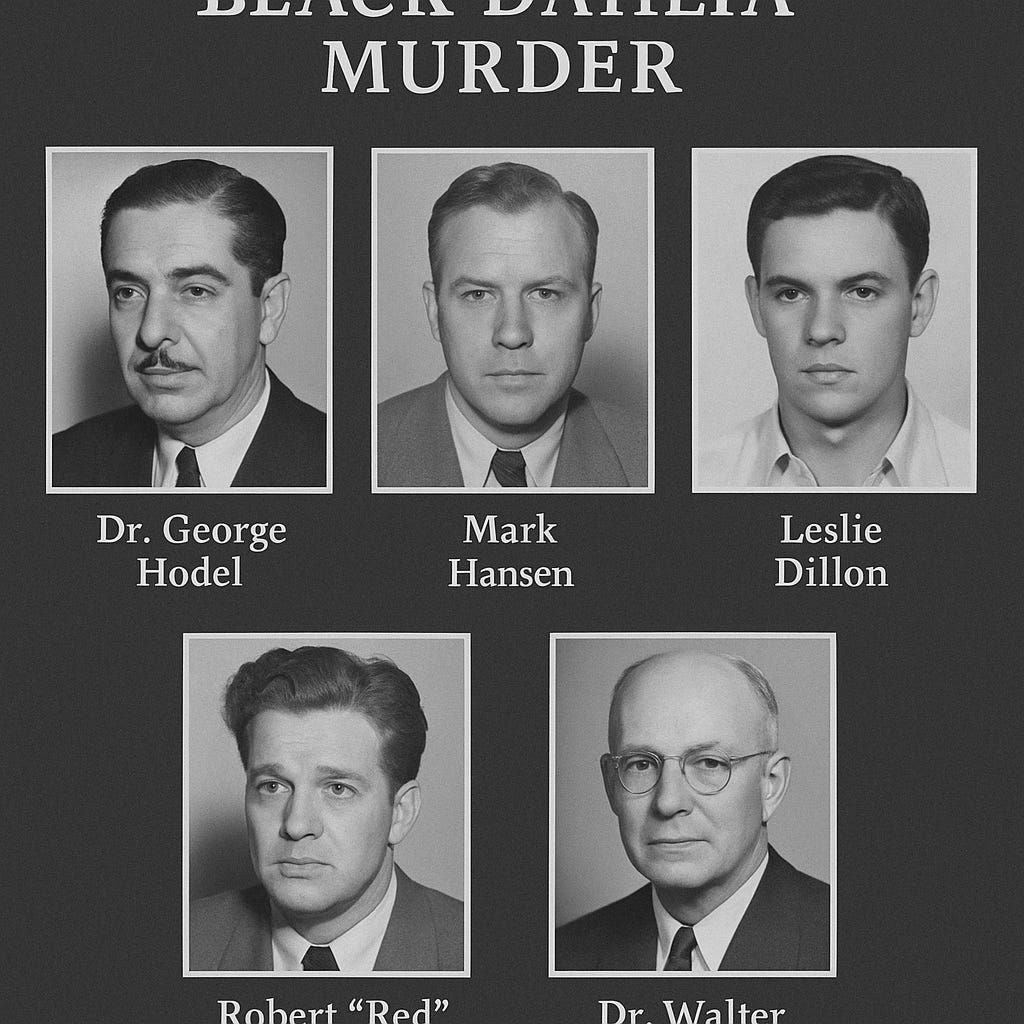

Then came Steve Hodel’s Black Dahlia Avenger (2003), which electrified the true-crime world. Hodel, a retired LAPD homicide detective, argued that his own father — Dr. George Hodel — was the killer. He produced handwriting analysis, photos, and transcripts of secret wiretaps, persuading some law enforcement veterans that he had solved the case. Others dismissed it as circumstantial. Regardless, the book dominated headlines and gave the Dahlia myth a new suspect and new notoriety (People).

More recently, William J. Mann’s Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood (2024) reframed the story within its broader cultural context. Mann argued that the Black Dahlia wasn’t just about one woman’s murder but about how Los Angeles itself — its media, its police, its entertainment machine — needed her to be a story. Critics praised it for cutting through decades of sensationalism to show the cultural machinery that produced the myth (NetGalley reviews).

And the publishing cycle isn’t over. In October 2025, Eli Frankel’s Sisters in Death will attempt to link Short’s killing with another unsolved case, promising fresh documents and overlooked connections. It is already generating advance buzz in outlets like People and Publishers Weekly.

📚 The Black Dahlia Reading List: How Books Kept the Mystery Alive

A curated guide for readers who want to explore the case beyond the headlines.

🔍 Nonfiction Accounts

Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder — John Gilmore (1994)

One of the earliest and most atmospheric deep dives into the case; influential, though criticized for blending fact with speculation.Childhood Shadows — Mary Pacios (1999)

A personal memoir from someone who knew Short in life; challenges the tabloid caricatures and humanizes Elizabeth.Black Dahlia Avenger — Steve Hodel (2003)

A retired LAPD detective accuses his own father, Dr. George Hodel, of the murder. Controversial but headline-grabbing, it reshaped public suspicion.Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood — William J. Mann (2024)

Reframes the case as a cultural phenomenon, showing how media, police, and Hollywood myth-making distorted Short’s story.Sisters in Death — Eli Frankel (2025, forthcoming)

A new investigation linking the Black Dahlia murder to another unsolved case, promising fresh documents and revelations.

Seventy-eight years after people found Elizabeth Short’s body under the pale winter sun, the mystery of the Black Dahlia remains unsolved. But what endures is not only the crime — it is the way the story has been told. In 1947, the press trampled evidence, interviewed witnesses before police, and christened her with a name that turned a young woman into a character. Headlines like “Girl Victim of Sex Fiend Found Slain” sold papers, but they also blurred truth, forever entwining Elizabeth Short with the mythology of noir Los Angeles.

In the decades that followed, books replaced newspapers as the loudest voices. Some tried to solve the case, others turned it into fiction, and a few fought to humanize Elizabeth herself. Together they reveal a second truth: the Black Dahlia is not just an unsolved murder, but a cultural mirror. Each retelling — from Gilmore’s atmospheric Severed to Ellroy’s fever-dream novel to Mann’s cultural critique — reflects more about the era that produced it than the crime itself.

And perhaps that is why the case endures. Elizabeth Short may never receive justice in the courts, but she has become eternal in print. First a victim of a brutal crime, then a victim of the press, she is now preserved in stories — tragic, haunting, and unresolved.

The Black Dahlia case might remain unsolved, but it may prove that the media's judgment can be stronger than any jury's.

📑 Sources & Further Reading

🌦️ Historical Records

Extreme Weather Watch. Los Angeles Weather Records, January 15, 1947. Link

📰 Newspapers & Media Coverage

Los Angeles Times. “Girl Victim of Sex Fiend Found Slain.” Jan. 16, 1947. Archive summary

Los Angeles Herald-Express. “Girl Tortured and Slain; Hacked Nude Body Found in LA Lot.” Jan. 15, 1947. (Referenced in case histories; contemporary coverage not digitized in full)

Golden Globes. Forgotten Hollywood Mystery: The Black Dahlia Killing. Link

🏛️ Official Records

Federal Bureau of Investigation. Famous Cases & Criminals: The Black Dahlia. FBI Case Summary

📚 Books & Author Accounts

Gilmore, John. Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder. Amok Books, 1994. Reviewed in The Horror Zine.

Pacios, Mary. Childhood Shadows: The Hidden Story of the Black Dahlia Murder. Millennium Press, 1999.

Ellroy, James. The Black Dahlia. Mysterious Press, 1987.

Hodel, Steve. Black Dahlia Avenger. HarperCollins, 2003. Coverage via People.

Mann, William J. Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood. Harper, 2024. Reviewed on NetGalley.

Frankel, Eli. Sisters in Death. (forthcoming, 2025). Preview in People.

🎙️ Commentary & Historians

Mann, William J. Quoted from Black Dahlia: Murder, Monsters, and Madness in Midcentury Hollywood (2024).

Pacios, Mary. Commentary in Childhood Shadows (1999).

Reward for Information

City Councilman Lloyd G. Davies offered a $10,000 reward for any information leading to the capture of Elizabeth Short's killer — equivalent to approximately $140,820 in 2024 dollars, according to Wikipedia.

Want to Submit a Tip?

If you believe you have relevant information about the Black Dahlia murder, you can still share it—anonymously and securely—through the following channels:

FBI Major Cases Tip Line

The FBI lists the Black Dahlia under their Major Cases and allows public tips:

You can submit a tip online via the FBI’s secure Tip Form.

You may also call 1‑800‑CALL‑FBI (225‑5324) to relay information over the phone.

Los Angeles Regional Crime Stoppers

For those preferring local anonymity:

Phone tip (anonymous): 1‑800‑222‑TIPS (8477).

Online submissions are available via their website, with full confidentiality guaranteed. They offer anonymous tip IDs and possible rewards, though identity is kept confidential.